- Home

- Nick Green

Cat Kin Page 2

Cat Kin Read online

Page 2

‘What have we here?’ Dad came in with Mum. Their smiles were like floodlights: bright and not quite realistic. ‘No tubes, no machines? Have we got the right room?’

‘Yeah.’ Stuart grinned. He looked unbearably pleased to see them. After hugging each in turn he lay back on his pillows, as if the effort had exhausted him. He seemed weaker than usual, Tiffany thought. And a lot pudgier than he used to be. The doctors had said that the medicines they gave him might do that. Still, he perked up when he saw the packet Dad was tearing open.

‘Tortilla chips! Gimme, gimme.’

‘These’ll have you back on your feet.’ Dad tossed the packet over and Stuart scrabbled for the ones that fell out. With some kids it was chocolate or crisps, with others it was the kind of toffees that tear out fillings. With Stuart it was spicy tortillas.

Tiffany munched one. ‘Hey. These are pretty good.’

‘They’re—mmmm—magic!’

‘What did you expect?’ Dad put on an affronted face. ‘Your mother only buys from the Tesco Finest range, the Sainsbury’s Taste the Difference range or the Waitrose Look On My Works, Ye Mighty, and Despair range.’

‘How are you feeling, sweetie?’ Mum’s smile hadn’t lasted.

‘They gave me the buzzy vest yesterday,’ said Stuart. ‘That’s pretty cool. It beats you lot thumping me on the back.’

The buzzy vest was a device that vibrated Stuart’s chest to help clear out all the gunk, because he couldn’t take deep breaths or even cough properly by himself.

‘You should come and listen,’ said Stuart. ‘When I sing with it on I sound like a robot.’

Mum looked worried, as if she had missed something important. ‘They make you sing?’

‘No, silly, I just do.’ Stuart laughed, then half-coughed for about a minute and went white. When he had recovered, he and Tiffany played Top Trumps. As usual, she tried to lose. Stuart found this tiring too. Holding the cards, he had once said, was like lifting bricks. Mum and Dad chatted to him, reeling off lots of news that even Tiffany found boring. Soon they began to run out of things to say. Kids, she could have told them, didn’t do small talk.

‘You’ll be home in a jiffy,’ said Dad. ‘I spoke to Dr Bijlani and he said he’s never seen anyone with MD shake off an infection so fast.’

‘Peter,’ Mum whispered, not so softly that they didn’t all hear.

‘So when we leave here on Tuesday, you might just be coming with us.’

‘Brilliant!’

Mum cleared her throat. ‘What Sanjeev actually said was…’

‘Cathy, just because he’s a doctor doesn’t mean he’s the expert.’

Even the crunch of chips briefly stopped.

‘I think you’ll find it does,’ said Mum.

‘What I mean is,’ said Dad, somehow raising his voice and speaking more quietly at the same time, ‘they don’t know everything. They always cover themselves. It’s like being optimistic is against the law.’

‘But there’s no point in—never mind.’ Mum clamped her mouth shut as if she had more to say, but not here.

Tiffany caught Stuart’s eye. The joy that had sparkled there when they arrived was fading. He had turned away from his parents to gaze at the ceiling, cool blue and painted with clouds.

‘Physical strength eighty,’ he murmured. ‘The Mighty Thor.’

‘Thirty-two. You win.’ Tiffany gave him her card.

She blanked out the car ride home. It was like a film she had seen too many times. Mum’s lines went something like, ‘You always make it worse by getting his hopes up,’ and Dad’s character always said, ‘But people get well faster if they believe they will.’ Tiffany was the silent extra no-one ever noticed.

She found proper solitude in her room. It didn’t last.

‘Tiffany,’ Mum called, ‘your kitty is curled up on your clean laundry. Sort it, please.’

Cat and clothes were piled on a kitchen chair. The prophet Muhammad, she knew, had once cut off part of his cloak rather than disturb a sleeping cat. Resigning herself to a less blessed life, she nudged Rufus aside and took the slightly hairy laundry upstairs. Her mood sank lower when she saw her black ballet leotard. Thursday was coming round again. She couldn’t fake a sore toe for the third week in a row. It had taken only a few lessons to unmask ballet as evil. Once she had loved watching ballerinas flit around on television. Now she hated it the way chickens must hate watching eagles. She was too tall, she was too clumsy; her pirouette resembled an out-of-control shopping trolley.

And then she remembered something worse. She had PE tomorrow.

‘Mummy. I think I’ve got a cold coming,’ she sniffed. Mum was preparing dinner.

‘Oh, shame. Do you think you’ll be well enough for school?’

‘’Spect so.’ Tiffany nodded bravely. ‘I don’t think I should do gym though. Can you write me a note?’

‘I don’t hear you sneezing.’ Dad had materialised in the doorway.

‘It’s just a tickle in my throat right now.’

‘A tickle. But it’ll be worse tomorrow?’

‘Yes.’

‘I see.’

Mum already had pen and paper in hand. ‘Who’s it to? Mrs Farmer?’

‘Miss Fuller.’

‘So, let me get this clear.’ Dad stroked his chin. ‘Your little brother is fighting muscular dystrophy on one side and pneumonia on the other, while you are laid low by a sniffle that isn’t even detectable to the outside world…oh, fine, fine, whatever.’ He retreated before Mum’s stare into the safety of the lounge. Mum scribbled the note defiantly and handed it over.

‘Best play it safe,’ she said. ‘After all, you don’t want to have to miss ballet again.’

Ugh. It was like rolling a boulder uphill. ‘Don’t I?’

‘You love ballet!’ Mum tweaked her nose.

Tiffany flinched. ‘I don’t. It’s embarrassing. And I wish you wouldn’t do that.’

‘What’s got into you?’

‘It’s just horrible. My joints don’t even bend right.’

Dad’s low whistle drifted in from the lounge. ‘Funny how these discoveries always come to light after the money’s been spent.’

‘Well.’ Mum mixed gravy in a jug. ‘You should go. Thursdays are Mummy and Daddy time, remember.’

‘Mother! I’m not a baby.’

‘Sorry, sweetheart. It’s not that we want to get rid of you. But we do have a lot on our plate. If we know you’re having fun doing something of your own, we can catch our breath once a week. Do you see?’

‘You want to get rid of me.’

Something boiled over on the stove. Mum rushed to it, blowing and mopping.

‘It’s just a Thursday thing, Tiffany,’ she sighed through the steam. ‘Is it so much to ask?’

Tiffany stalked out of the kitchen. ‘I am not doing ballet.’

The local paper crumpled beneath her on the bed. She scoured the Classified columns in rising despair. A watercolour painting club? She might fancy trying that, but none of them met on a Thursday. Girl Guides? Get lost. Junior Fitness Club? PE by another name. And kickboxing was right out. Her annoyance gave way to misery. She was too much of a weed even to give her parents one evening alone. Maybe she could develop an illness herself and get packed off to hospital. No. That was a horrible thing to think.

She turned the page. Hmm, Tae Kwon Do…was that the paper-folding one? She wouldn’t risk it. Tiffany kicked her pillow in frustration.

A ginger missile launched from the top of the wardrobe and splashed down on the duvet by her head. Rufus looked peeved at being granted such a soft landing. Startled only for a second, Tiffany hugged him to her. Here was a real gymnast, martial artist, ballet dancer, you name it. He could have done any class he liked (well, maybe not the painting club). Sad, she gazed into his amber eyes. It seemed that the only talent she had was loving her cat.

She glanced down at the newspaper. There was tiny advert in the corner that she hadn’t noticed

before. It was shaped like a pyramid.

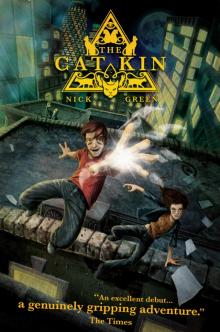

Cat Kin

Explore your feline spirit

Cat lovers and the curious all welcome

That sounded more like it! Not a stupid PE lesson. A proper club. People like her talking about their pets, sharing tips, swapping pictures maybe. She did wonder why the meeting place was Clissold Leisure Centre, but only for a moment. It was probably just a good place to hire a room.

Rufus was testing his claws on the newspaper. She tore out the ad before he could.

THE GREY CAT

Echoes from the squash courts perforated the dry, processed air. Sports centres made Ben nervous. No doubt the smell of chlorine awoke memories of clutching the poolside as a toddler. Now, crossing the lobby, he was even more anxious than usual. He couldn’t help thinking about what might be happening at home.

It was a stupid thought. It was not as if he could offer Mum the slightest protection if Stanford should appear again in a cloud of brimstone. She might cope better if he wasn’t there. At least they had a door now. It was light, flimsy wood, unpainted; easy to break, cheap to replace.

The muscle-bound man at reception noticed him, the way a bull in a field might. Ben found himself whispering.

‘Tae Kwon Do?’

The man tilted his shaven head, possibly meaning Go that way, more likely trying to ease cramp. Ben bruised his hip hurrying through the turnstile.

While he changed into tracksuit trousers and T-shirt he wondered again why he was here. Perhaps Mum thought it would take his mind off things. It was true that she always came home cheerful from her own self-defence class. But given the choice he would be at Dad’s flat, taking on the master himself on his home-made pinball machine, ignoring the furious neighbours who banged on the ceiling.

He wished Mum would swallow her pride and give Dad a call. Raymond Gallagher would tell Stanford where to go. Yet she had made Ben swear not to mention their problems to Dad. It was a tough promise. Dad always asked Ben questions. He wanted to know how Mum was getting along, if she needed anything, did she seem happy in her new job at the organics shop. If pressed for details, Ben would have to grit his teeth and say ‘Fine,’ over and over.

He left the changing area and climbed the stairs to the upper level. A girl with wavy brown hair was lingering by one of the small halls. She wasn’t dressed for sports and looked awkward in her jeans and black coat. It was the only free hall so Ben decided to wait there too, leaning on the other side of the doorway. The girl kept glancing down at Ben’s trainers. He was wondering if he should say hello when the texture of the air changed. He turned.

A grey-haired woman stood there, dressed as if for yoga. He hadn’t heard so much as a footstep and yet there she was. No taller than him, with neat features and eyes between brown and green, she might have been seventy or younger than fifty—her wiry build made it impossible to guess.

‘Are you here for the class?’

‘Yes,’ said Ben and the girl together.

‘How do you do. I’m Felicity Powell.’

She seemed to be waiting for something. Finally it clicked.

‘I’m Ben.’

‘Tiffany,’ said the girl, breathlessly. ‘Erm, is this–?’

‘Hmm.’ The woman looked them up and down. ‘I was expecting a few more. We’ll wait.’

She padded off down the corridor. Ben blinked and she was gone.

Minutes passed. Just as he was thinking he had made a mistake (what mistake, he wasn’t sure) the woman reappeared with several kids shuffling ahead of her. None wore martial arts gear and only two looked dressed for sports. A couple of them exchanged hesitant glances as if they already knew each other, if not to talk to. A girl in a blue gym suit had a newspaper tucked under one arm, and one boy, round-faced and wearing an anorak, was carrying a flat case like an artist’s portfolio. By the time they reached the hall he looked deeply confused.

‘Welcome to my class. My name is Felicity. You can call me Mrs Powell.’ The woman did not smile. The group edged closer together.

‘There’s been a mix-up,’ said Mrs Powell. ‘This hall has been double-booked. We’re going to move elsewhere.’

Without another word she led them down to the lobby. Feeling something wasn’t right, Ben glanced back up at the balcony. A line of youths clad in white tunics were filing into the free hall. It was the Tae Kwon Do class.

Before he could blurt out that he had joined the wrong group, he was stepping through the glass doors into the evening light. Why had they come outside? The girl in the black coat trotted to keep up with Mrs Powell.

‘Excuse me. Where are we going?’

‘To my studio, Tiffany. I live just here.’

Ben was sure he’d misheard. Not Theobald Mansions? Uh-oh, she was. She was heading for the flats that lurked next to the leisure centre. These blocks were long overdue for the wrecking-ball. Brown as old blood, broken-windowed, painted with pigeon muck; the idea that they might harbour life would be beyond the wildest dreams of NASA’s scientists.

Mrs Powell unlocked the main door and went in. Ben followed the girl into a hall webbed with graffiti. He climbed a staircase that reeked of cigarettes and urine. The others were drawn along behind him, their footsteps resounding off the walls.

Where was Mrs Powell taking them? Who was she? And why in the name of sanity were they still following her? Fear rose in Ben’s throat. This was not normal. Not normal at all. He tried to relax. One old lady had to be fairly harmless. Whoever she was, she couldn’t abduct seven kids. Not alone.

It was only when Mrs Powell had opened the door to the top-floor flat and was ushering them inside, and Ben was actually stepping inside, into this stranger’s home, that the thought struck him like a thunderbolt: maybe she wasn’t alone.

Even as he woke up to what he’d done, he heard the door lock behind them.

Cobwebs, queasy smells, the mouldering skeletons of small animals underfoot—these were just some of the things he expected to find and did not. Fright gave way to surprise. Mrs Powell’s flat was bright and spacious and spotlessly clean. She led them into a room that could have swallowed the lounge at home twice over. It was one big wooden floor with not a carpet, chair or speck of dust to be seen.

‘This is my studio. Find a space and sit down.’

Something about her voice made obedience automatic. Ben sat cross-legged.

‘Not like that. Kneel. Sit on your heels. That’s it. Hands on the floor in front of you. Don’t slouch. Good. From now on, this is what sit means.’

Mrs Powell sat likewise. She surveyed them, moving her head not her eyes.

‘You may be wondering—ah. Jim has decided to join us. You are honoured.’

A cat trotted into the room, bead curtains rustling in its wake. It had the sort of coat rich women used to kill for: lush, smoky grey, dappled black in a leopardish pattern. It clocked the group with one crystalline glance before settling near Tiffany like one of the group. That was when Ben realised. The strange way they were kneeling was just how the grey cat sat.

The round-faced boy scrambled to his feet.

‘Sorry, Miss. I think I’m in the wrong class–’

‘Sit down.’

The boy folded up again.

‘Do you know what I teach here?’ the lady asked.

In the hush Ben could hear buses rumbling down the main road. Tiffany raised a hand.

‘Mrs Powell…’

‘Yes?’

‘It’s to do with cats, isn’t it?’

‘It is to do with cats.’

Tiffany beamed and went on staring at the grey cat, her eyes wide and shining as if the animal were made of solid gold and not hair. The oriental girl in the blue gym suit raised her rolled-up newspaper to get attention.

‘That’s not what I heard,’ she said. ‘I thought it was a kind of tai chi.’

That opened the floodgates. Soon everyone was talking, firing off questions as fast as Mrs Powell could ask their names. A girl call

ed Cecile thought Cat Kin was a London nature trail. A tall boy, Yusuf, who spoke like an American, said he was after the Big Cats Conservation League. Nobody could agree. Daniel, a small black kid in glasses whom Ben vaguely recognised from school, had been sure he was joining a dance group. And Olly, the boy who’d tried to leave, had for some unfathomable reason believed he was going to an art class to draw animals. Why he had thought it would take place at Clissold Leisure Centre, Ben never discovered.

‘You appear confused.’ Mrs Powell’s voice brought instant hush. ‘And yet all of you are right. What you will learn at Cat Kin is somewhat akin to dance. It isn’t unlike tai chi. And it will bring you closer to nature. Even Oliver here isn’t totally off the mark: we will be copying an animal. What we shall do together is pashki.’

Mrs Powell stood up in a single fluid movement.

‘Pashki. One of the most ancient disciplines of body and soul. For more than–’

‘I’ve never heard of it,’ put in Susie, the oriental girl.

‘You are about to,’ said Mrs Powell softly. Ben got the feeling that only a very foolish person would interrupt her again. ‘You all know what yoga is? Perhaps you have heard that many movements in yoga are inspired by the animal kingdom. In particular, cats. You’ve seen how cats stretch and flex themselves—ah, speak of the devil.’

Her cat was reaching out his long, wicked claws, shivering in ecstasy.

‘Cats do this to maintain their physique. Unlike humans, cats don’t need to go to the gym. You might say that Jim is his own gym.’ She didn’t smile. A few in the group laughed nervously.

‘Long ago in Egypt,’ said Mrs Powell, ‘people worshipped the cat. They called it Mau—for obvious reasons. The goddess was named, variously, Bast, Pakhet, or Pasht.’

‘Excuse me.’ It seemed Tiffany couldn’t help herself. ‘That’s where we get the word “puss” from, isn’t it?’

Ben tensed, but this time the interruption was welcome.

‘Yes! Look, Jim, we have a cat scholar among us.’

The grey cat actually turned his head towards Tiffany and his tail flicked. Ben squirmed involuntarily. That animal gave him the creeps. And all this kneeling was making the arches of his feet hurt like crazy.

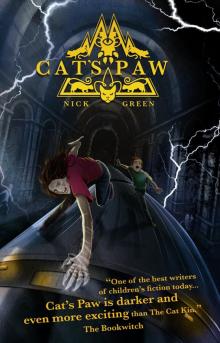

Cat's Paw

Cat's Paw Cat Kin

Cat Kin