- Home

- Nick Green

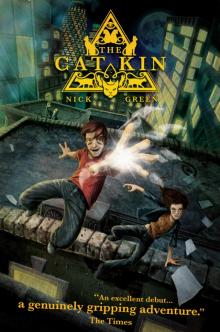

Cat Kin

Cat Kin Read online

Published by

Strident Publishing Ltd

22 Strathwhillan Drive

The Orchard, Hairmyres

East Kilbride G75 8GT

Tel: +44 (0)1355 220588

[email protected]

www.stridentpublishing.co.uk

First published by Faber and Faber, 2007

This edition by Strident Publishing Limited, 2010

Text © Nick Green, 2007

Illustrations © Lawrence Mann, 2010

The author has asserted his moral right under the Design, Patents and copyright Act, 1988 to be identified as the Author of this Work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-905537-16-7

eISBN 978-1-905-537-73-0

Typeset in Bembo

Designed by Sallie Moffat

Contents

1. VERMIN

2. ANYTHING BUT BALLET

3. THE GREY CAT

4. ONLY NATURE’S OWN

5. DEATH RAY

6. FELINE FACES

7. CLAWMARKS

8. FALL ON YOUR FEET

9. THE UNINVITED GUEST

10. THE FUNNY FARM

11. LOCKED OUT

12. MONSTERS IN THE ATTIC

13. DECLAWED

14. MOTHER CAT’S SECRET

15. INTO THE PRISON

16. FIGHT OR FLIGHT

17. LOST

18. A PURER SOURCE

19. DARKNESS AND DAY

20. NO WAY IN

21. CAT AND MOUSE

22. EIGHT LIVES

23. THE FINAL CURTAIN

VERMIN

When Ben got home from school he found something good, something bad, and something worse. The bad thing was that he had lost his front door key. The good thing was that he didn’t need it, because the door was already open. The worse thing was, it was not merely open but smashed off its hinges.

Ben felt sick. He stood in the lobby until the silence convinced him that whoever had done this was not inside the flat. He went in and turned automatically to shut the door. Unable even to do this, he wandered in a daze to the fridge and got himself an orange squash. He was sitting on the sofa sucking the glass when he heard Mum’s feet in the corridor. A very loud swear word echoed off the bare plaster walls.

‘Ben! Are you okay? Ben!’

‘Mum.’ He stood up as she ran into the lounge.

‘What did—’ Mum was silent for about thirty seconds, her lips pressed white. Then she exploded like Vesuvius.

‘How dare you? How dare you? Who do you think you are?’

She went on in this fashion until Ben heard himself stammering, ‘I’m sorry, Mum.’

Her eyes nailed him. ‘What? Sorry? Why are you saying sorry?’

Ben didn’t know. He shook his head. Tears were fighting to get out and it was taking all his strength to stop them. Mum balled her fists and glared at the splintered door.

‘Stanford. Damn Stanford!’ She used a string of words Ben never even thought she knew. ‘I can smell him all over this. It stinks of him!’

She dealt the ruined door a kick.

‘Mum.’ Ben looked at his hands. He was wringing them. Up till now he’d only ever done that to his swimming things. ‘Mum, sit down. I’ll put the kettle on.’

‘That’s it. That really is it. I’m calling the police. He’s had it now. They’ll pin it on him even if he was fifty miles away.’

Ben filled the kettle, all he could do, while she paced the lounge like a caged animal. He noticed that, although she was shaking the telephone as if it were a weapon, she was not dialling. He poured hot water onto the teabags and heard the phone slam down. Then the bathroom door slamming shut. Then the sound of Mum crying while trying to make no sound at all.

She was not going to call the police. Because, of course, they had just found out what happened when you did.

Ben could barely recall the lost golden age (really just a couple of months ago) when Stanford had been merely a word on a letter, and not a name to place alongside Hitler and Satan. That first letter had gone into the bin since it obviously didn’t apply to them. Dear valued tenant, blah blah. We regret to inform you that the tenancy period of your flat is due to expire subject to Clause 18c of your agreement. We must therefore request that you terminate your occupancy by 30th August and so on. With these jaw-breaking phrases it seemed to be saying that the tenants in the block had to move out. But Mum wasn’t a tenant. She and Dad had bought this flat from the landlord, Stanford and Associates, four years previously. So that was all right.

Ben forgot about it until another letter hit the mat one frosty Saturday morning. It was from Stanford and Associates. It offered to buy the flat back for a certain price. Mum spluttered into her grapefruit juice.

‘Are they mad? We paid thirty thousand more than that!’ She laughed as if it were a joke and tore the letter up, then ranted about it morning and night until Ben learned to tune out. He had other things, like his homework, his sadistic French teacher and the brand-new pinball machine at the arcade to worry about. A short while later Mum got a phone call Ben didn’t hear, except for her very loud ‘No thank you!’ at the end.

Then the aggro started. Someone’s burglar alarm went off all weekend, driving them bananas. Mum finally went looking for it, found it belonged to the nearby derelict factory and used the bread-knife to cut its cable. Some days later, piles of rubbish began collecting in their tiny garden. Eventually Ben spotted a bunch of teenage boys dumping bin-bags over their wall and peeing on the flowerbed. He raised his phone to video them and they scarpered.

One evening Ben took a phone message from a Mr John Stanford. He wanted to stop by and ‘discuss the sale’. Somehow he booked himself in for the Friday. Mum flipped at first but decided, in the end, that if this guy had trouble hearing the word No then he could come round and read her lips.

John Stanford was tall with sandy blond hair. He wore a smart suit. His smile was bright, revealing hidden wrinkles in his young-seeming face. Following him into the flat came a tree-trunk of a man (‘This is Toby,’) not at all suited to his name. Stanford laughed and joked about the weather and shook Ben’s hand. He asked Mum if she wanted a cup of tea. Taken by surprise, Mum said yes. Stanford sent Toby into the kitchen. Mum looked on, flummoxed, as this huge stranger made tea in her kitchen with her cups. He didn’t know where anything was, either, so there was much banging of cupboards. When she said, ‘I’ll do it,’ Stanford seemed not to hear.

‘What about you?’ he said to Ben. ‘Lemonade?’

Ben had his bearings by now. He said, ‘No, thanks.’

Toby brought the tea and a plate of biscuits, which he placed near Stanford. Mum grimaced as she sipped hers. It clearly had sugar in it.

John Stanford settled down to business. He said he would increase his initial offer on the flat. Mum reacted as if he’d spat at her. Stanford lit a cigar, ignoring her grunt of distaste.

‘Mrs. Gallagher.’ He spoke in a clipped, polished way. ‘This property isn’t nearly so desirable as you think. Not with kids running amuck and leaving litter everywhere.’

Toby slurped his tea in the silence. Stanford allowed smoke to curl up around him.

‘Tell you what. I’ll give you till midnight on Monday. You can call my mobile. After that, my offer drops by a thousand every day I don’t hear from you. So think about it, Mrs. Gallagher.’ Mum’s face had no colour in it. Stanford’s wrinkled with another smile. ‘At least do it for your son.’

‘Leave him out of it!’

‘It wasn’t I who brought him into it. All I’m saying is that this area is growing less and less like somewhere I’d want to raise my own children. And the longer we wait, the less desirable it

’s going to be.’

He laid his still-burning cigar upon a cushion, one that Mum had embroidered herself. When he picked it up, a black crater gaped in the fabric.

Mum told him to leave. Stanford finished his tea and biscuits and nodded to Toby. The men breezed out as smoothly as they had arrived. Mum burst with a shriek of rage. That was when they’d called the police, who did precisely zilch, as far as Ben could make out. And now they had no front door.

‘Look out, Ben!’

He’d already seen the danger. He hammered at the button and the flipper winged the steel ball before it could plummet into oblivion.

‘Yay, Gallagher!’

He cradled the ball in the right flipper, let it roll and flicked it at a deflector. It rebounded into a multiplyer zone and buzzed around like a trapped hornet. His score piled up. He kept a weather-eye on it. Not too much. Not today.

Ben’s reputation as a pinball wizard had spread like head-lice around his school, and beyond. The new craze for the old-fashioned machines meant contests were a regular thing. Ben’s advantage, aside from quick reflexes and an unusual ability to watch the ball no matter how fast it ricocheted around, was that his father was obsessed with the game and had even built a pinball table from scratch, which he kept at his own flat.

‘Come on, Ben,’ Alistair urged. ‘Make us rich. You’re destroying that sucker.’

Other friends chipped in with cheers of encouragement. Glancing to his left (and a fair way up) he caught Cannon’s eye. Cannon—real name William Canning, nickname a no-brainer—gave him a warning wink. Ben carefully sent the ball into a low-scoring area.

Normally he wouldn’t dream of doing this. He hated the idea of letting everyone down. Many bets got placed on these games and most people here had a couple of quid on him winning, as usual. But Cannon had offered him twenty pounds to throw the match. (‘You’ve got to make it look real,’ the huge boy insisted. ‘I want you to almost win.’ And I want a titanium front door and a Kalashnikov, Ben had thought at the time, but it ain’t gonna happen.) However Cannon had been, well, insistent, so Ben reluctantly decided he could stay in one piece and give Mum the money towards the new door—he planned to slip it into her purse so she wouldn’t know it came from him.

‘Hit the reactor again. The reactor!’ Rajesh gibbered, jumping up and down.

Ben fired the ball at it and missed, deliberately. He thought how dumbfounded everyone would be when he lost on his favourite table. It was called Fort Osiris and the setting was secret agents storming an enemy’s lair. How this scenario related to the abstract way the ball spasmed around the board, he couldn’t guess—but the concept appealed to him.

Groans swept the arcade as he let himself drop the ball. He had one more shot left.

A droplet fell from his nose and splashed a red star on the bathroom’s decorated tiles. Just then Mum rustled in through the cardboard barrier they’d rigged up as a substitute door. He knelt, dabbing up the blood with a tissue. Mum wouldn’t want her mosaic of a giant seashell stained—she’d slaved over that every evening for two weeks.

‘Sweetie! What happened to you?’

‘Football accident.’ He sniffed, trying not to bleed in front of her. ‘I bumped into the goalie.’

‘Are you sure?’ Mum peered at him. The bruises on his face were already darkening. ‘Have you been playing with those yobs from school?’

‘We don’t play…we hang out.’

‘You’re lucky your teeth aren’t hanging out. I can’t afford dentists as well as carpenters, you know.’ Mum tutted, then hugged him. ‘At least you’re brave about it.’

Later, tucking into his fish fingers, he felt her eyes on him again.

‘Ben. This isn’t about…You aren’t doing that pinball nonsense still?’

‘Of course not.’ Ben drank quickly from his water glass. What an idiot he’d been. As his last ball rolled harmlessly towards the gully, a reflex had taken over and sent it hurtling back up the board. His safety margin vanished in a barrage of lights and he had beaten his opponent’s score by a measly 200 points. And then, outside the arcade, Cannon had beaten him.

Mum picked at her Marmite on toast, about the only meal he saw her eating these days. She looked tired and hollow-cheeked as she continued to give him suspicious glances.

‘I won’t have you doing it, do you hear?’

‘Mum! I stopped ages ago.’

‘Good. So how are you spending your free time now?’

Ben tried to think. If you took out school and the arcade, his mind was a blank.

‘I’ve got the computer. I like time by myself.’

‘You need to get out more. And I don’t mean with those bus-stop kids. The leisure centre’s just down the road.’

‘We do enough swimming at school.’

‘Do something else then. The man who takes my self-defence course is starting Tae Kwon Do classes for kids. Why not try that? It’d be a great way to meet new friends.’

Ah. Now he recognised the signs. She’d been looking for a chance to suggest this.

‘I don’t need to learn self-defence.’ He winced as a bit of ketchup stung his cut lip.

‘Ben, I’m not nagging,’ said Mum. ‘I worry, that’s all. This time it was the front door. Next time…’

‘Oh yeah. Like a kid with a bit of kung fu could duff up Stanford’s heavies.’

‘Not exactly.’ Mum held his gaze. ‘I don’t mean a big thug like the one who came here. Stanford would be sneakier than that. He bribed those yobs to dump litter in our garden. That mightn’t be all they’re prepared to do.’

‘Mum!’ She was scaring him now. ‘Okay. I might check the class out. If you want.’

‘Only if you want.’ She touched his hand across the table. ‘We’ll be all right, Ben. No-one’s going to force us into anything. This is our home.’

It hurt to smile.

ANYTHING BUT BALLET

The highlight of the dog’s morning had been nosing inside a bin, so when the cat appeared it was like winning the Lottery. A mongrel, part Alsatian, part hearth rug, it hurtled along the gutter two strides behind a ginger streak. The cat leapt onto the bonnet of a blue Volkswagen, its fur standing in spikes as if frozen by an icy wind.

The dog barked in triumph, making experimental jumps at the car. The cat retreated up the windscreen, hissing and arching like electricity. Half-crazed with joy, the dog got its front paws on the bumper.

It recoiled as if stung by a spark. The cat had flashed across the bonnet and clawed its nose. More horrified than hurt, the dog ran in circles, yelping. The door of the nearest house opened and a lanky, brown-haired girl ran out.

‘Oi! Pack it in, fleabags!’

Sensing that the fun was over, the dog slunk away.

‘Ssshh, Rufus. It’s gone.’ Tiffany Maine scooped the cat off the car. Rufus changed from feline fury to fluffbundle, squinting with pleasure as he let himself be carried baby-style into the house. He gave Tiffany’s hand a sandpapery lick.

Cats didn’t, of course, do this. Cats didn’t care for people the way dogs did. Cats were selfish and cold, neither giving love nor welcoming it. What rubbish. Tiffany got cross when she heard people saying that. If any dog was more friendly, more needy, or more doting on humans than her cat Rufus, she had never met one. But still people refused to see it, purely because they didn’t expect to.

‘Tiffany! Do shift yourself. We’ll be late.’ Her mother was calling up the stairs, not noticing Tiffany right behind her, getting a free hair-styling from Rufus’s tongue. ‘Oh, you’re there. Shoes on? Where’s your coat?’

‘It’s the first day of spring.’

Her mother tutted. ‘The year has no business going by so fast. Peter!’

‘Hang on. We’re about to break a world record here. Five, six…aha!’ Tiffany’s father hurried downstairs, both hands bristling with mugs. ‘Tiffany, unless the dwarves are visiting I think seven cups in your room is excessive.’ He vanished into the kitchen

.

‘Come on, Peter.’

‘Cathy, the hospital won’t fly away if we’re five minutes late.’

‘But he’ll be waiting.’

Dad swept into the hall with a jingle of car keys. ‘It’s a good job then that I was ready half an hour ago. Tiffany, put the creature down, he’s not coming.’

The hospital’s logo was the face of a crying child forever on the point of cheering up but, Tiffany noticed, never quite managing it. In spite of this the place felt less like a hospital than a huge playhouse. A helter-skelter stood where the receptionist should have been and a shiny red bus looked as if it had wandered in off the street. Only the unnaturally clean smell made her uneasy.

They still knew the way to Lion ward blindfold, even though Stuart had been living mostly at home these past months. He had enjoyed learning to use his electric wheelchair, pretending to be a comic-book super-villain, and Tiffany had been glad to help out in her own way. Not many big sisters were actively encouraged to thump their little brother repeatedly on the back every day.

Tiffany had once had tonsillitis for a whole fortnight and had feared she would never get better. But Stuart had been ill for two years. Shortly after he turned six he had begun to fall down a lot in the playground. He complained all the time that he was tired and kept getting terrible coughs. Soon he was walking strangely; then he had trouble walking at all. Tiffany had watched at first with pity, then impatience, then horror when she realised this was no silly phase. Looking back, she believed Mum and Dad had always known far more than they had told her. She’d had to work out for herself what was happening to her brother.

Tiffany reached his room first, creeping her hand round the door. She heard Stuart’s cry of delight above the burble of Sunday morning television. He was sitting up in bed, pale but grinning, waving a deck of cards.

‘Best of three!’ he demanded, by way of saying hello. The pack was Superhero Top Trumps, an old favourite. Tiffany settled on the bedside beanbag and shuffled the cards. Stuart sighed. Probably he had spent all morning arranging them.

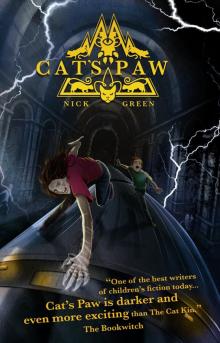

Cat's Paw

Cat's Paw Cat Kin

Cat Kin